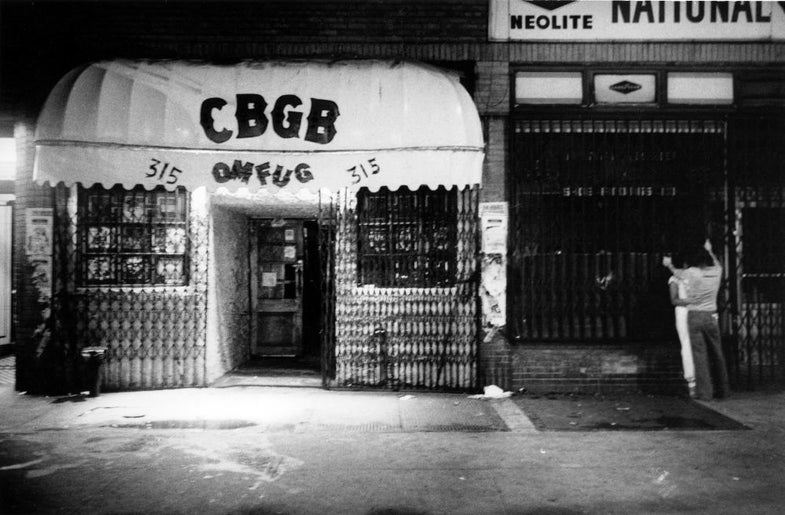

David Godlis’ Secret New York of the 1970s

This winter New York punk photographer David Godlis will release his first book: a collection of photographs taken at CBGB...

This winter New York punk photographer David Godlis will release his first book: a collection of photographs taken at CBGB from 1976-1979. Heavy on grain and taken using the ambient light of the famed night club, Godlis captured early iconic images of Blondie, Talking Heads, Ramones, Patti Smith and all the other regulars who were hanging out on the Bowery in the late ’70s.

Although the Kickstarter-funded project passed its goal weeks ago, the campaign still has 21 days left (and recently passed $95,000). Donating will get you a first edition copy of the book.

Godlis talked to American Photo about crowd funding, Robert Frank’s influence and what it was like shooting live music with long exposures and steady hands.

You passed your $30,000 Kickstarter goal three days into your campaign for this book. Did you expect things to happen so quickly?

I realized people enjoyed seeing my pictures. Almost every night I post on Facebook and there is always some kind of dialogue if I post something old that [my friends] haven’t seen. I’ll post a picture of Link Ray at CBGB and they’ll go “Oh my God! Where is your book?” And I go like, “Don’t ask me.” There have been near misses that have happened with it, but I sort of thought this way was the way to do it.

When I launched, I sat there and I just went, “Um what do I do now?” I shared with Facebook friends first, then I picked 80 of my most important email people. I couldn’t handle going through my entire email list. I did both of those the first night and then it just started to take off. People on Facebook got so excited and kept passing it on. I can’t believe I picked 40 days, but I didn’t think I would get it this quick.

It sounds like this book was a long time in the making…

I was always thinking of it as a book, when I started shooting this stuff realizing it was a project it was just like a no brainer. Photo books were like records for me at the time. The Diane Arbus monograph, that seemed to me like the perfect book. It was always going to be a book. It just sat around for a while.

Had you tried to get it published as a book before?

Sure, I tried to get it published, but it is kind of this in-between thing. To try to sell it as a book, everybody wanted it as a music book—not as an art photo book. I just held out because I never wanted it as anything but an art photo book. It took a while for the art photo community to get what was happening in that club was art—it wasn’t just rock and roll that was going to disappear.

When I shot these things, it wasn’t considered cool to photograph musicians if you were in art school. In fact, people looked down on me a little bit. I was a street photographer, I was shooting like Robert Frank, Gary Wiinogrand, Lee Friedlander and people were like, “Why are you wasting your time on musicians?”

How did you start shooting the CBGB scene?

I was a street photographer and I moved to New York to look for work. I loved doing street photography. That was my thing. I got a job, and all of the sudden I couldn’t be out during the day and shooting as much. I also needed a place to hang and meet people. What I had always done in Boston, before I got to New York, was go to a club that had music. I loved music. I sort of figured out that CBGB looked like an interesting place. I’d seen some ads in the Village Voice that looked really cool for bands that had weird names. I went in and I realized, this is the place I want to hang out.

The first time I walked in there I heard the band Television and I was like okay, they’ve got the same Velvet Underground albums as me. Nobody had Velvet Underground albums back then. You only had them if you bought them in the ‘60s and you kept them. There was a clan of people who had Velvet Underground albums, and I walked into that club and it was like, “Ah, here is where the clan is.”

A few nights after I started hanging there I had one of those ah-ha moments at the bar. Brassai’s Secret Paris of the 30s had just come out and I was fascinated by that book. I just went, “Oh, I could be doing street photographs at night here.” I can figure out how to take pictures at night here. I never really thought about being a music photographer, I didn’t go there to be a music photographer, I went there to hear music.

How long did it take you to figure out how to shoot in the club? What were the challenges?

I had a Leica camera that I was shooting my street photographs with, and I just sort of tried to hold it steady at slow speeds. It was all experimental and it took a couple of weeks to figure it out, but by the time I figured it out, I was rolling. There was also only just so much brainpower on a given night when you are drinking and hanging out.

The thing that was hard is I was using the same roll of film for outdoors and indoors most of the time. I was pushing the film like crazy. I was shooting on stage at probably 1/30 at f/5.6, 1/15 at f/8 and I was shooting out on the street 1/4 at f/5.6. If things moved really fast on stage, like the Ramones, I’d move it up to 1/60. I would shoot to get something on the film, and I was kind of developing the look in the darkroom.

You mentioned the work of Brassai and Diane Arbus, what else was influencing your pictures back then?

I spent a lot of time staring at album covers when I was a kid and a teenager. I read the photo credits. I knew who did the cover of the Dylan album and I knew who did the pictures of the Beatles and I knew who did the pictures of Jimmy Hendrix, I knew all those things. I also had an intense interest in the art of photography and had spent years before I walked into CBGB looking at pictures about the history of photography. Those things factored in to the way that I constructed my pictures. I can see Robert Frank’s pictures in some of mine.

For me, [Robert Frank’s] photograph of the kids in front of the jukebox, I always sort of walked into CBGB and it had a jukebox and it had a pinball machine and it had a bunch of, as Patti Smith called them, “Just Kids” hanging out. And that was almost the picture I kept trying to take. Not a literal picture of people in front of the jukebox, but that feel. That is what I was looking for.

Seems like an interesting mixture of modern pop culture influences and traditional photo influences.

Absolutely. I was 26 and everything I had been influenced by, just like somebody’s first record album, it just came all out of me when I walked into that scene. Every little influence that I had just came right out. For me, these photographs were just like a critical moment. It took a while to convince people that is what they were.

What are some of your favorite images from the collection?

Every picture has kind of these interesting side bar stories.

Patti Smith is probably my most known picture, the Patti Smith on Bowery in front of the Bleecker sign—I love that one. For me it just doesn’t ever seem to get old and Patti is still as important if not more important as she was back then. Still, nobody knows who is on the left side of that picture. All of us who hung out there, at least two or three people have told me it is them.

The series of no wave punks on the car that I did in the summer of 1978 is a real favorite. I came out of CBGB and they were all sitting there and they are all kind of significant players in the no wave scene and they were just sitting there. It was almost like they were waiting there for someone to take their picture. I love that one.

I’m going to try to incorporate stories into the book, especially the things that are showing up from this Kickstarter campaign on my Facebook page. There are just some great stories. People remember things I don’t remember and remember their own version of whatever that night was.

Performers like Patti Smith and the Ramones make for some great shots, what else were you interested in capturing at CBGB?

I didn’t just photograph the stars. My thing is to photograph everybody. Even I’ll add in Hilly Kristal, because without him none of it would have happened. The picture of Hilly that I have, I photographed him out on the street while he is kind of working the gathering of the crowd for a nights show. I would show my pictures back then to people and people who weren’t part of that scene, they’d be like, “Oh you have all these pictures of punk Patti Smith, punk Blondie, punk Talking Heads, punk Suicide, punk Richard Hell” and then they would see this guy in a beard and a flannel shirt. And they would go, “What is that in your series?” I’d go, “That’s the guy who owned the club.” I thought I should have the bartender, the waitresses, the owner of the club and I should have the bathroom—that kind of thing.

What happens next? When do you expect the books to go out to your Kickstarter backers?

The book is sort of taking shape as I’m running the campaign. Now that I’ve passed the goal I can actually forge ahead. Hopefully it moves along and we have it by Christmas. We are going to move fast. It’s not like I don’t know what I’m doing here, what I want. The edit is pretty much there.

When you look at these pictures now what do they make you think of?

I feel really good that I did it. I feel really good that I shot it, the way that I shot it. I could have easily shot it with a flash and probably made more money. For me, the work has held up to my own standards. I don’t get sick of the pictures. And that was the goal. Don’t print up the ones you are going to get sick of, don’t print up the ones that almost make it. I’m really glad that people enjoy them—especially the people that were there— I’m like their family photographer or something.