Curator Sarah Greenough on 25 Years of Photography at the National Gallery of Art

Talking time, memory, history, and the role of contemporary images in a museum

Contemporary photography came relatively late to the National Gallery of Art, but its first major exhibition of recent work, “The Memory of Time: Contemporary Photographs at the National Gallery of Art,” acquired with the Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund, packs a wallop. On view at the Washington, D.C. museum through Sept. 13, 2015, the show is one of several exhibitions and events celebrating the 25th anniversary of the National Gallery’s photography department. It brings together a wealth of photographic works, many of them unique objects, from artists such as Chuck Close, Carrie Mae Weems, Adam Fuss, Sally Mann, Sophie Calle, and Chris McCaw, to name just a few.

American Photo’s editor-in-chief, Miriam Leuchter, spoke with Sarah Greenough, senior curator and head of the department of photographs at the National Gallery of Art about the show and her institution’s approach to contemporary photography.

The Memory of Time will be on view until mid-September, but unlike some of your exhibitions, it won’t travel to other museums. So far I’ve seen it only through the catalogue (published by Thames & Hudson). It looks great, but I really want to get to Washington to see the show in person.

For many of these things, the size of the pieces matters so much and of course you can’t really get that through a printed reproduction. Many of them are just huge— the Vera Lutter and the Subotzky & Waterhouse Ponte City pieces are enormous— and that scale really affects how you respond to the work. It is a show that needs to be seen. We are pleased with how the catalogue turned out, but I always encourage looking at the original objects.

And your photography department is only 25 years old?

Photographs first came to the National Gallery in 1949 when Georgia O’Keefe donated the large and important key set of Alfred Stieglitz’s photographs—1600 Stieglitz photographs—but no more additions were made to the photography collection. I got there in 1978 and was charged with organizing and accessioning the Stieglitz collection, and once that was done we then did a series of photography exhibitions in the ’80s that directed more attention to photography. It was as a result of those shows that in 1990 the trustees decided that we could finally start collecting photography, 151 years after photography was announced.

How does contemporary photography fit in with your program?

We haven’t done a lot with contemporary photography in the past. In 1989 we did a big survey show, “On the Art of Fixing a Shadow,” which celebrated the 150th anniversary of the announcement of the process of photography, and that included work from 1839 to 1989. Since then we’ve shown contemporary photography, but more when it has been by established photographers—for example, Harry Callahan or Robert Frank. But we’ve never had an exhibition that has focused exclusively on contemporary photography until this one.

It feels like a real statement to me. The way you’ve chosen and organized these photos makes it seem as if you’re trying to say something about the role of photography now and the museum’s relationship to photography now. Is that fair?

Yes, I think it’s fair. We’re certainly not suggesting that this is a survey of everything that’s going on in contemporary photography. We’ve used the issues of time and memory and history as a way of focusing our acquisitions and the exhibition because we felt that a number of photographers were exploring these issues, but it is certainly not representing everything that is going on, and we don’t claim that it is in any way.

I think it would be hard to represent everything that is going on! But it is interesting to look at these trends and the historiography that’s happening in this show—it feels very cogent.

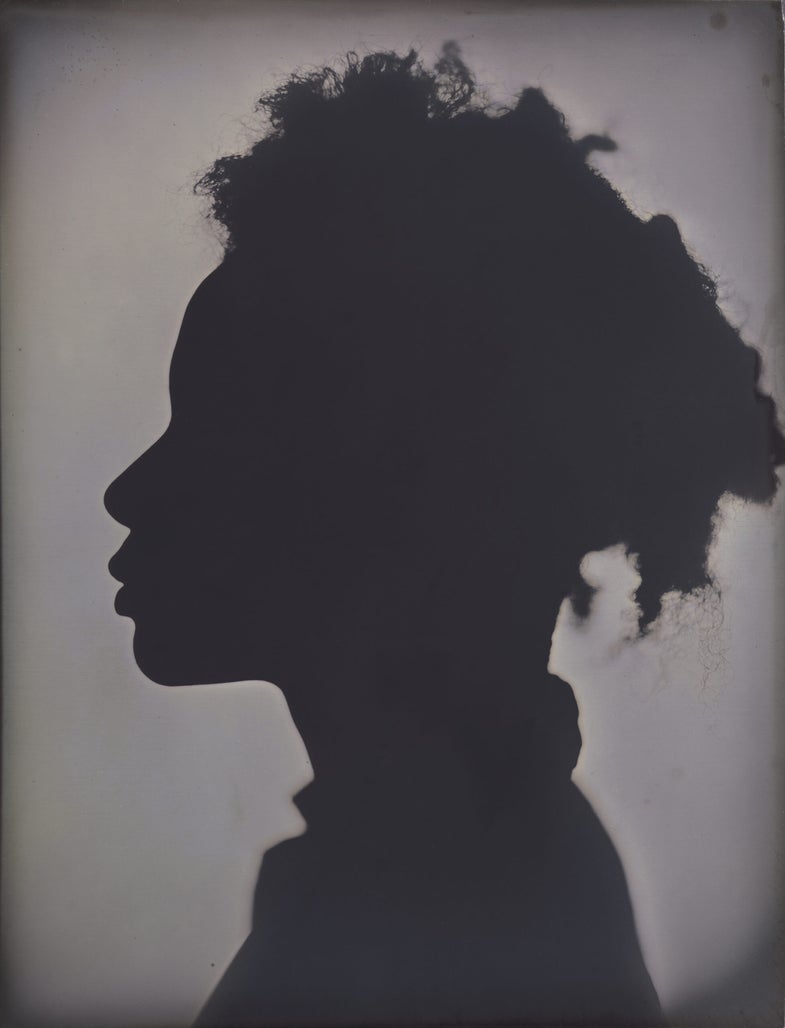

Well, I do feel that a lot of contemporary photographers are looking at the history of photography and questioning how older photographs have informed our contemporary understandings, for example, of race. You certainly see that in the Myra Greene photographs, where she used that older 19th century printing process, the ambrotype, to allude to photography’s historical role in teaching people how to see African-Americans not as individuals but as racial types.

But, I think the exhibition also shows contemporary photographers are interested in history and the passage of time more broadly, not only in how it relates to the history of photography. Carrie Mae Weems reflects on how African Americans have been presented not just in photographs but in paintings, as well—the title of one in the show is “After Manet,” so you know she is looking back to 19th century painting and thinking about how African-Americans were or were not included in that representation. And the exhibition also includes a lot of works where other photographers are looking at broader issues related to history, like Mark Ruwedel showing us the impact of 19th century railroads on the 20th and 21st century landscape, reminding us of the impact that our western expansion had on the land itself.

That speaks also to your notion of archives and how the idea of a collection comes into play for some of these photographers.

A number of photographers in the show recognized that that history is not a set and defined one, but that the archive—those collections of material—can be mined from a number of points of view and histories extracted from them. We have a very beautiful and evocative piece by the Vietnamese-American photographer Binh Danh who went back to the genocide museum that’s now in Phnom Penh on the site where the Khmer Rouge had killed many of their victims. The Khmer Rouge had this bizarre habit of photographing many of the people before they executed them. Binh Danh re-photographed many of these, not as the sort of quick, casual snapshots that the Khmer Rouge had done, but as unique daguerreotypes, giving a sense of pride and importance to these people who for the Khmer Rouge were just numbers to be executed.

There’s also a fascinating piece by Susan Meiselas in which were she documented the history of one of her own photographs as it has moved around the world. First came this picture that she took in Nicaragua in 1979 called “The Molotov Man,” which shows a Sandinista rebel about to hurl a Molotov cocktail. She then traced how that image had been appropriated by many different factions over the years, both pro-Sandinista forces and anti-Sandinista forces, even by the Catholic church, showing how this one image served all these different purposes. It was even screened onto the walls of buildings and then later painted out. It’s a fascinating record of the impact that a single photograph can have and how we can all interpret it in very different ways.

There are a lot of singular works in this group, both installations and unique pieces such as daguerreotypes. Why is that?

Photographers like Sally Mann and Myra Greene, who are exploring older photographic processes—daguerreotypes, ambrotypes—those are by their very nature unique objects. Then there are also people like Vera Lutter and Chris McCaw who are making in a sense direct positives. Vera Lutter photographs directly onto large sheets of paper for her camera obscura images and then not making prints from them. That was a very conscious decision on her part: She wanted to capture the direct image that is in the back of the camera obscura, so she doesn’t make prints. Chris McCaw also photographs directly onto photographic paper, not negative film because he’s using such high-powered lenses and found that the intensity of the sun was so strong that it would burn through the photographic paper and he wanted to have that actual mark of the sun on his images. So for them it is part and parcel of the process. For me, though, as a curator, it speaks to the fact that we were so lucky to be able to get these works now. If we didn’t get them now, chances are that we wouldn’t have had that second chance to get them later on because they are unique works and there aren’t multiple prints out there.

Some of these photographers don’t use a camera at all. Alison Rossiter and Christian Marclay, for instance.

Christian Marclay is using the photogram process, which is of course as old as Henry Fox Talbot. Alison Rossiter does something very different, sort of exploring what happens to photographic paper as it ages over time, an absolutely fascinating idea that has yielded some beautiful prints.

In some works, there is a hybridization of digital media and the physical print or object. But it’s fascinating to me how little a role digital photography seems to play in this collection considering the past 25 years.

I think it is there, but subtly. Some of the photographers do work digitally and then print their works using more traditional analog methods.

Idris Kahn’s “Houses of Parliament, London, 2012” is a great example of that.

Exactly. And even with images that are being captured digitally, if one is exhibiting in a museum a print, you usually have an inkjet print, not based on traditional analog photography but at least a print itself. I don’t see this [show] as a turning away from digital photography. I think in part it might be a function of the age of some of the artists in the exhibition. I think the oldest is Chuck Close and the youngest is probably Matthew Brandt. But probably the bulk of them are in their 50s and 60s. If we were doing an exhibition of, say, more photographers in their 30s and even 40s I think you would see a lot more digital photography—digitally captured inkjet prints, probably.

Looking at this exhibition not just as an anniversary but as a signpost for the future, what do you see both for the National Gallery and for photography?

As far as the Gallery is concerned, we will certainly continue to be actively involved in contemporary photography. As far as what the future of photography is, where does it go, I couldn’t possibly answer that question. Photography has been constantly changing throughout its entire history, adapting, and as each new technological change comes along, it seems to prompt new ways of thinking about and looking at the world. We’re obviously at the beginning of the digital age and we’re starting to see some of the changes that it’s provoking, and those will only continue in the future. The medium has changed so much over time, and digital is yet just one more change in its evolution. The fact that photography continues to be so strong and vital I think is just further indication of what a profoundly important medium it is for us.