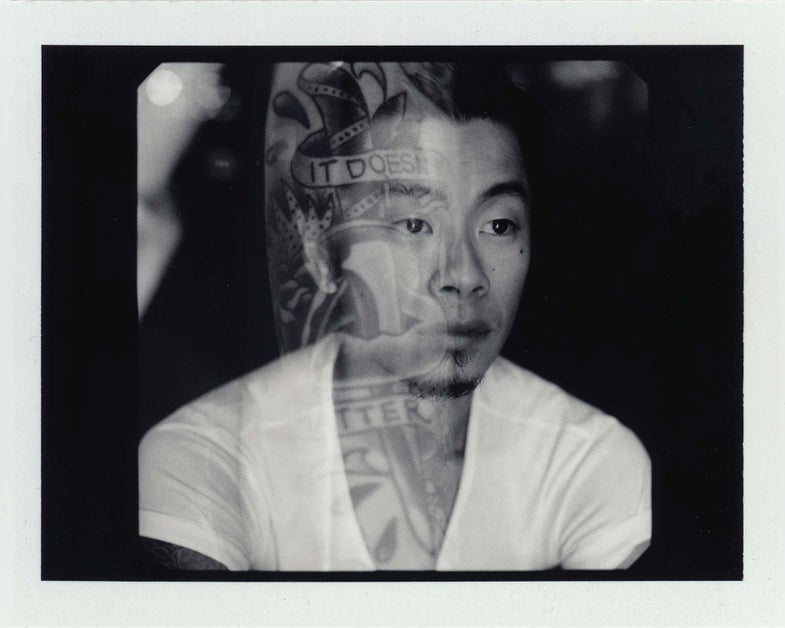

Capturing Intimate Portraits of Tattoo Artists and their Tattoos on Film

Carmen Chan showcases her unique style using double exposures

Fashion photographer Carmen Chan has been embraced by brands such as Puma, J. Crew, Burberry, and DKNY. When the culture site Hypebeast asked her to share some personal work, she turned to her friends, a group of artists at Star Crossed Tattoo in Hong Kong.

“It’s really brave to get a tattoo,” she said. “I became enamored by them.” So she picked up her Mamiya RZ67 medium-format film camera and started making portraits. The assignment-turned-project, It Doesn’t Matter, looks at the intimate relationships between individuals and their ink.

“Tattoos are as much about a person as a face is,” Chan says. “They are as revealing as a portrait, if not more so.” People get tattoos for all sorts of reasons: to rebel against authority; to announce their beliefs; to support a cause, as with the Semicolon Tattoo Project; or simply to adorn their bodies. Whatever the reason, Chan notes, “it’s very personal.”

Using Fujifilm FP3000B black-and-white pull-apart instant film, Chan captures the faces and the tattoos of her subjects in a double exposure. A setting on the camera allows her to push the shutter as often as she likes without advancing the film—a deceptively simple technique that takes a practiced eye to create art with. The self-taught photographer says that getting the positioning just right can take a couple of tries, but usually no more than five frames.

In these portraits, each sitter’s expression reads clearly as their tattoo hovers ghostlike nearby. A sketch of roses on a woman’s hip is positioned to embrace her profile. As a man glances pensively downward, his superimposed tiger tattoo rests on his shoulder and wraps around his head, unleashing fangs and claws. Some of Chan’s subjects appear defiant, chin raised; others have a faraway sadness flickering in their eyes; all are introspective.

She named her project for one of her subjects’ tattoos, an anthem crowning a full sleeve of ink. “I guess ‘It doesn’t matter’ started off as something that was cynical and nihilistic,” the sitter said when Chan asked him about its meaning. “But over the past five years, it’s evolved into something entirely opposite. I’ve discovered that on the flip side of ‘It doesn’t matter,’ the positive side of existentialism, lies endless possibility. I bear the responsibility of a happy life; I get to choose.”