Books of the Year: Michael Northrup’s Babe

In 2002, Michael Northrup met photographer and publisher Jason Fulford of J&L Books through a mutual friend, the graphic designer...

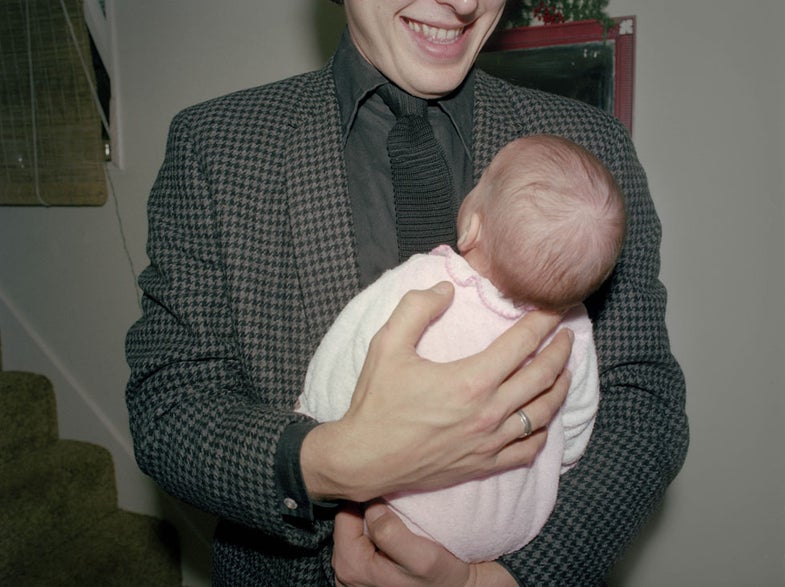

In 2002, Michael Northrup met photographer and publisher Jason Fulford of J&L Books through a mutual friend, the graphic designer Paul Sahre. Fulford was struck by the unique perspective on midwestern family life he found in Northrup’s snapshots from the 1970s and ’80s, and soon after, they collaborated with Sahre on a book, Beautiful Ecstasy_. Northrup’s archive has plenty to offer: this year, J&L released his second book,_ Babe_, one of our favorite books of 2012. It’s yet another example of an experienced photographer’s archives (Northrup is 64) being revisited in today’s fruitful publishing world, surfacing interesting work for a new generation. I called Northrup at his Baltimore home studio last week to talk about the book._

How did this book come about?

As Jason got his publishing thing going (J&L Books), he came down to Baltimore with Paul [Sahre] around 2002, and they just went up to the top floor of the house and rifled through a ton of prints I had from the 80s. And they grabbed about 20 or 30 and took them back to NY.

Paul told me, and I consider this an ultimate compliment, that on their drive back up, Jason had to pull over he was so shaken by the work–I can’t remember exactly how he put it, but here was this epiphany and appreciation of the work where he literally had to pull over for about five minutes. That really bonded Jason and me, and I just let him have it. And they did the total edit on that one [the first book, Beautiful Ecstasy] and Paul was involved in the design. The newest one is all Jason. He went through the same period of work, did the entire edit himself, and then I got this book in the mail, and there you go. I had really no say, nor did I want to—I just wanted to leave that up to Jason.

I tell people that I can take pictures, but after that I have no idea what to do with them, and it shows. I don’t really push for showing the work, I’m not really aggressive with it. I just do this out of the love for it, and hopefully somebody will see it and do something with it.

You’re also a commercial photographer, is that right?

Yeah, but it’s down to two clients now. I have a guy in D.C. who is an art director at a large magazine group, and he hires me a couple times a month. And the City Paper here [in Baltimore] hires me for jobs around once a week, and that’s probably my favorite client of all time. The art director sends me an email and just says “go shoot this” and I go shoot it, whatever I want to do with it. I have this wonderful access to people, with carte blanche. And of course the photos show up at like 80 dots per inch, black and white, so that’s not why I do it. Not for the press. It’s to get access to people. I have like 10 to 20 minutes with them, that’s usually all I get. It’s a real challenge, but from that I’ve got a whole slew of portraits that I really love.

I grew up in the midwest in an American family, just like the people in the book, and what drew me to your photos was that I found them able to communicate really clearly this quality of families as these weird, scary, funny, dangerous things.

It’s interesting you picked up on that. Where were you from in the Midwest?

I grew up in Indiana.

Well, that’s almost the same as me. I grew up in Ohio. And almost all of these images are from Ohio, so you’re hitting the nail on the head—I guess that comes through. My wife says there’s a quality of time here, of a certain age. A lot of the pictures are very figurative without anything specifically dated–there’s no cars, no clothing, no haircuts, but it still has this kind of antiquated element to it. I didn’t feel this in my work, but I’m always interested in why people look at my pictures, and I was very curious how you happened to take my book. I learn from that.

Has your view of your own work changed as you’ve seen it recontextualized by another person in a book?

You know, I don’t think so. Every picture was made one picture at a time. I’m not a real heavy, intellectualizing person. I pretty much live my life from the gut. And that sometimes comes back to bite my butt, but in my photography, oftentimes it allows me to capture something quickly, without having any pretense. My pictures aren’t created from an idea–they’re usually something I’ve discovered.

From Babe

Your sense of composition is very attractive to me, and that’s something you don’t always see in the snapshot aesthetic. Some of these moments are almost miraculous in how the elements form together in the frame.

In a lot of my earlier work, often I’d cut people’s eyes off, or crop a picture so you could just see their mouth, so I wasn’t interested in people, I was interested in a figure. At that time, the figurative quality of the image was more important than anything literal in it, and that still sticks with me. Over the years, [as a student and teacher of photography] I was lucky to have access to some of the greatest living photographers of the time [Minor White, Jack Welpott, Brett Weston]. That made me deeply appreciative of the structure of images, because all of them preached that to me, either indirectly or directly.

When you’re looking at someone else’s snapshots, I think a natural thing to do is imagine the circumstance under which they are taken. To ask yourself “What’s happening in this photo.” The photo of the barbecue really did that for me–I look at that, and I want to know what’s going on.

It’s funny you bring up that word “what,” because I think that really is at the heart of a lot of these. It’s “What the hell? What the fuck is this?” Often times I’ll tell [my subjects] “Hey, do this” and they’ll ask why, and I’ll say “I don’t know, just do it.” And a lot of times I don’t even know why. But I guess I’m trying to trigger exactly what you’re responding to, that moment of “what?”

Tell me about the light painting technique that’s in a few of these photos.

It started with my love of on-camera flash back in the 1970s when I was shooting black and white, and the quality of light, things illuminated out of darkness in circles of light. Diane Arbus did this shot—and I’ll never forget it—of the Jewish giant with his parents, and he’s towering over them, and it’s this hard-edged circle of light.

Jewish Giant at Home with his Parents

In the ’80s I shifted to color when it became available to the common person, and everybody that I was going through school with [at the Art Instituted of Chicago] jumped on it. I was having real problems shooting color after doing black and white for ten years, shooting corny stuff. One of the great advisors who was there said “why don’t you just shoot like you did with your black and white?” And once that happened, I just fell in love with it. I started using a gel over the flash out in normal daylight, just to hit someone really hard with it while they were surrounded with normal-looking light. And then I took it the next step with multiple exposures, flashing a couple different spots. By the mid ’80s I made it a real elaborate thing, where I was strobing interiors with color over maybe 400 different exposures. Multiple exposures and strobes allowed me to light-paint in a normally lit environment, and I took that to the -nth degree.

From Babe

When you look through these photos again, do they represent to you a memory of a specific day or a specific event?

Oh my God, yeah. Around 2002 I realized I had to scan all these negatives because they were really starting to deteriorate. It took me two years, scanning almost every day. I was going through my life, and I know exactly, for every shot, the life that was going on around that moment. Almost all of these people in the book I’ve had a personal relationship with.

You just reminded me of another heavy influence, a book done by Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan called Evidence [Sultan and Mandel’s new retrospective is also on our 2012 best-of list]. What it was simply were file photos from NASA, or Kraft foods, or God knows what, but they were pulled out of context. And when you do that, it elevates them to something special. And that probably is also key in my photos, that each one of these experiences are isolated and removed from any kind of context, and that creates a kind of mystery, for me. And tying that in with the snapshot aesthetic, and all the formalism I was taught, it’s just a big brew of influences that all kind of coagulate into what you’re looking at.

So this book feels really autobiographical to you I’m sure, even though it’s been made through another person’s point of view?

Oh yeah, there’s no getting rid of that. Each shot I remember the day, and I carry that with me every time I look at these.

With my parents, humor was going around all the time, and it was contagious. Underneath a lot of these photos is not a real serious person trying make something that will invoke some serious idea–I’m just having a blast, that’s all. I’m cracking up on these things, but I think the way [my photos] are composed, I’m just trying to put [these moments] up on a higher level than just a simple record.

That joy comes through, I think.

Good.