Books of the Year: Anton Corbijn, Waits/Corbjin

Anton Corbijn has been making portraits of famous artists for five decades. He’s directed feature films and dozens of music...

Anton Corbijn has been making portraits of famous artists for five decades. He’s directed feature films and dozens of music videos, but he is likely best known for his extremely personal rock and roll portraits. Cutting his teeth shooting rock stars for the New Musical Express in the 70s, he evolved to provide creative direction for the likes of U2 and Depeche Mode, building relationships over many years that are still fruitful to this day—his video for Depeche Mode’s “Should Be Higher” was released earlier this year.

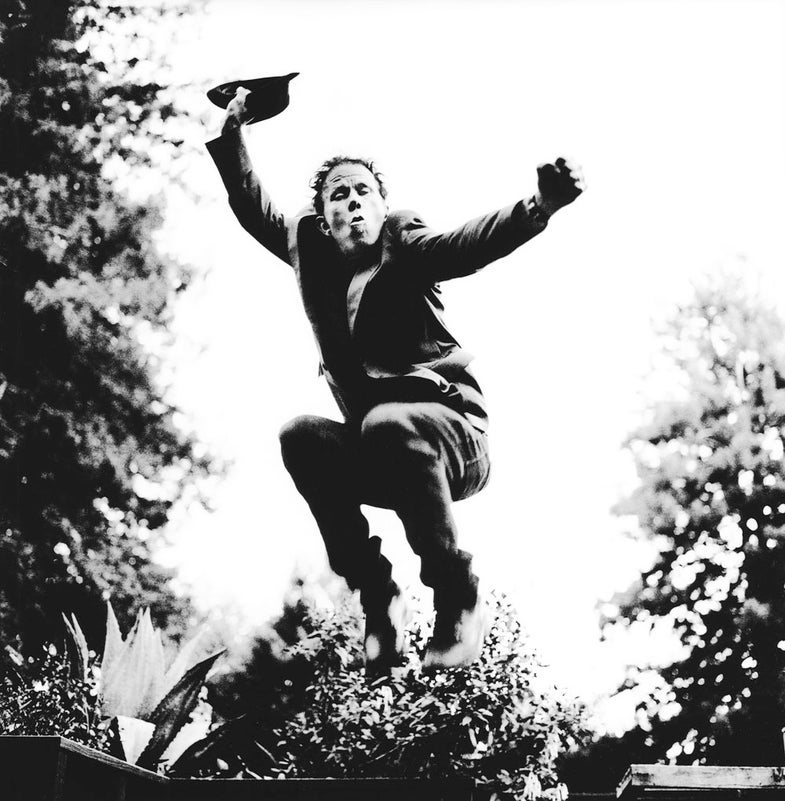

But WAITS/CORBIJN ’77-’11 (Schirmer/Mosel) is a document that chronicles his relationship with the less famous, if no less talented, bourbon-soaked troubadour Tom Waits. For 35 years, Waits worked exclusively with Corbijn, leaving the Dutch photographer with a bevy of images to edit down to the 226 that made the book. Their friendship is apparent, and the deep trust developed between the two over the years allows for some extremely expressive, if not always revealing, portraits of the gravel-voiced singer/songwriter/actor.

The book’s final pages find Waits wearing yet another hat, featuring his photographs, poems, stories, and collages—meant to serve as a companion to the work Corbijn made with Waits as his subject. American Photo spoke with Corbijn about the book—whose limited hardcover edition sold out in nine days—and what it’s like to shoot such a colorful storyteller.

How did you and Tom first meet?

Backstage at a concert, when I was a young photographer in the ’70s. But it really started up in ’82, ’83. He really liked the work I had done with Captain Beefheart, a hero of his. It became a more serious relation, rather than a guy from a magazine trying to photograph him all the time. We became friends over the years. I think we liked working together, whether it was press pictures, or because we were at the same place at the same time. It was very playful, generally. I’m always trying to photograph where you can’t tell if I paid to take the photograph or they paid me to take the photograph. There were many instances where we did meet and didn’t take pictures.

What birthed the idea for the book?

There was never an idea, of course. It was just something that came up after I realized I had so many pictures of Tom. There was never a plan, that’s the beauty of it. There’s a lot of gaps in the book. It doesn’t try to say I photographed Tom beautifully, or this is Tom Waits life. All the book says is this is what Tom and me do together, and this is how Tom looks at things. His own art. Which is unique, I think. I don’t think Tom ever showed anything like that. He kept quite a raw perspective. A deep perspective of how Tom functions, and where his eyes go to, and what makes him tick.

How did you go about sequencing the images?

I’m a photographer, I’m not a music journalist or anything. I’m a portrait photographer, and I work with artists, whether they’re painters or magicians or movie actors or directors or whatever. It’s always the work that has the function of a magnet for me; I like to meet people behind the work that I like. So no, I didn’t cut it up to be specific about something. Because it’s always Tom, and Tom tells stories, and he acts stories, and that’s what the pictures show. There’s a few pictures that come close, maybe, to the private Tom, but basically it’s Tom as an artist. But you can see we’re very relaxed with each other.

Is this a book about Tom, or a book about you and Tom?

I think it’s more about my relationship with Tom. I don’t think the images necessarily fit into the periods of music that he’s doing. He comes up with an idea, I come up with an idea for photographs, and it’s very low key. There’s no makeup, no management, not even an assistant. Just him and me driving around and doing stuff. It’s grown up men that don’t want to grow up. It’s very nice.

Tell me more about Tom’s art that’s featured in the book

Instead of having text explaining some stuff, we thought it would be nice to get an idea that’s closer to Tom’s mind, or how he thinks, by having his own work. You can get a lot from that, I think. That’s how it was set up, and it was very interesting. I really liked what Tom did, I love the perspective he puts on the stuff, the little stories that go with the photographs. They’re very funny.

Do you see things similar to the way Tom does?

I’m very much like the son of a protestant minister. I think he’s a lot freer in his mind. In my pictures, I always do more than just make an image, I try to convey something, if I can. I don’t think Tom wants to do that, by definition. He has fun with the picture he takes, and the picture tells enough.

How tough was it to edit down 40 years of work?

In the early days, I didn’t have a lot of money, so I didn’t photograph that much. I took a picture here, a picture there. In the later years, I photographed a lot more. Some time was spent cutting down the later years, because I had so much material…for 2002, I couldn’t have 40 pages of just one year, so some fell by the wayside. It’s hard to take a bad picture of Tom, even for me. I’ve tried very much to take bad pictures, but it’s hard.