Books: A War-Torn Region’s Story Told Through Soccer

Most of you reading this have probably never heard of Nagorno Karabakh, an unrecognized republic roughly the size of Maine...

Most of you reading this have probably never heard of Nagorno Karabakh, an unrecognized republic roughly the size of Maine nestled between Armenia and Azerbaijan. I hadn’t either, before I picked up Offside: Football in Exile, a unique photobook that tells the story of this war-torn region via its two main soccer clubs, FK Qarabag Agdam and FK Karabakh Stepanakert. We watch this story unfold via the lives of six individuals and their complex relationship with both their tumultuous homeland and the game of soccer.

Offside: Football In Exile

As the Soviet Union disintegrated in the early 1990s, Nagorno Karabakh became one of many violent flashpoints in the broader regional conflict in the Caucasus, with Armenia and Azerbaijan both battling fiercely for control of its territory. The confusion continues until this day–Nagorno Karabakh functions as an unrecognized de facto republic, and the conflict has displaced hundreds of thousands of Armenians and Azerbaijanis alike.

It’s a complicated story, to say the least. It’s wise, then, that photographer Dirk-Jan Visser and journalist Arthur Huizinga chose to narrow the story’s focus down to six lives. In Offside we meet people like Aslan Kerimov, a veteran defender for the Azerbaijani team FK Qarabag Agdam. In 1993, the team was driven from their home stadium in the heart of the disputed territory due to the violence (only in 2009 did they return to the region, from their temporary home in the Azerbaijani city of Baku). His story contrasts with David Martirosyan, a 19-year-old Armenian goalkeeper whose father was killed in the war, and whose future in the sport is uncertain, considering that the major European soccer sanctioning bodies ban his unrecognized homeland and its biggest team, FK Karabakh Stepanakert, from official competition beyond the junior level.

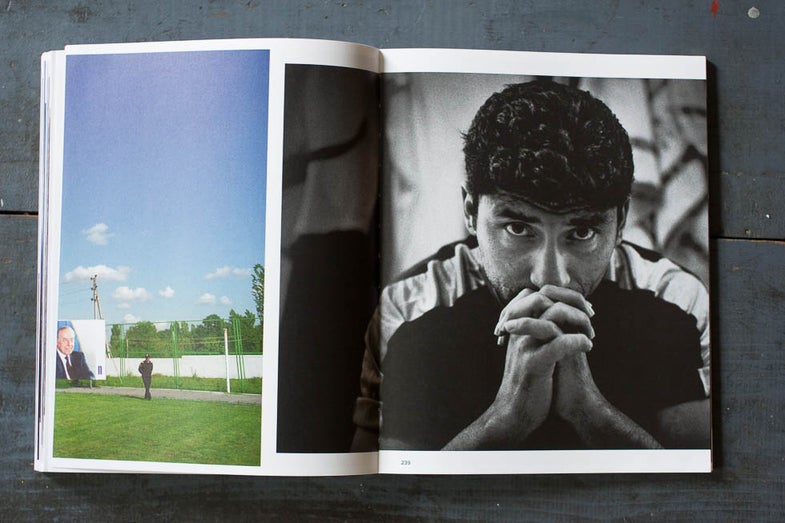

The book is organized around the six lives it describes, and its design features do a lot to drive the overall storytelling. Each section is introduced with a written biography by Huizinga and caption list, with all text printed in English, Armenian and Azerbaijani. The texts are also color-coded to indicate the person’s ethnic heritage (blue for Armenia, red for Azarbaijan). Visser’s photos that follow are also rigidly segmented–with photographs of important places and landscapes in color, and depictions of each person’s daily life in stark black and white. His work is presented alongside personal snapshots from years’ past provided by the subjects. The photos are often broken up across consecutive pages, with no image seen in its entirety on any single page.

Watch a video trailer made for the book and project.

At first I was a bit overwhelmed by these design choices–I felt like I couldn’t immediately solve the various puzzles the book seemed to be presenting. But of course this is intentional–you’ll not find a more complex and frustrating story to try to tell than the decades of ethnic and political conflict that have shaped this part of the world, and in presenting their stories in such a rigidly systematic way, Visser and Huizinga both emphasize this fact and at the same time attempt to impose some form of order on the chaos. I found it hardest to come around to the photos being broken up across multiple pages; the work here is often beautiful, and it was frustrating to feel deprived of any single image’s full impact. But again, the lives these photos depict could not be more fragmented, and the choice to break them up effectively mirrors that.

Ultimately I really enjoyed this book for its full-on commitment to narrative storytelling. Photographers experimenting within the documentary tradition will often shy away from communicating any single interpretation of their work. And that’s fine—forcing the viewer to interpret a series of images presented wordlessly can be a powerfully effective way to create an emotional response. I find this approach most effective in a gallery or museum setting. But in the case of Offside, Visser and Huizinga have made a work that is very much a book, exemplifying all the narrative strengths of the medium in fine form.

Offside: Football In Exile was published by Paradox and Y Books. A gallery show with some of the work was shown in the Netherlands at Noorderlicht gallery earlier this year.