Best Photobooks of the Year: 2015

Our annual roundup of the year's finest photobooks

Wheeler captures the funky side of the Northwest, in all its post-punk glory before the coffee shop-laptop hipsters settled in. Released through the self-pub, merit-based distribution outlet Minor Matters, Wheeler’s book reveals the marginalized characters of its title—from an unabashedly feminine perspective. “They talked about the male gaze in art. Why can’t women have their own gaze?” she says. “That’s some of what this book is about. It’s a conceptual feminist manifesto for the Wild West.”

This lavish portfolio of JR’s public art includes a cartoon strip that begins: “Growing up on the outskirts of Paris, while still in high school, JR starts leaving his mark,” then shows the tagging and graffiti pranks that morphed into elaborate photo-based murals, bringing global acclaim to the artist. The photobook goes on to trace JR’s most ambitious outdoor works, from creation to (in some cases) disassembly—the source photos, mounting techniques, grand results, and public reactions of photo projects from “Women are Heroes” spread across the walls of favelas in Rio to “Inside Out Project” in New York’s Times Square. The collected work illustrates JR’s creed that the street is “the largest art gallery in the world.”

Light’s aerial images of the terrain surrounding Las Vegas are both gorgeous and disturbing, showing the suburban sprawl from such heights that it looks like abstract art but reveals manmade havoc. In and around the U.S. city that perhaps best symbolizes the burst of the housing bubble in the Aughts—Nevada was the fastest-growing state in the nation prior to the 2008 crash—we now see half-finished neighborhoods, empty cul-de-sacs, oversize castle homes, and lush golf courses surrounded by barren desert, all evidence of real estate speculation run amuck. Yet as with his other aerial work, Light makes it look weirdly beautiful.

This is Lynsey Addario‘s powerful first-hand history of the first decade of the 21st century and a candid exploration of the motivation and judgement of those who documented it. Framed with her 2011 kidnapping in Libya, and resolved with the birth of her son less than a year later, the book tracks her navigating between two radically divergent worlds, taking us from the battlefield with Kalashnikov fire hanging overhead to the beaches of Bosphorus and Mexico, the foreign-correspondent wine parties, the days between assignments spent “decompressing” with significant others. It offers a profound and refreshing perspective as a female combat narrative.

Vrba creates enigmatic images that grab the eye with their artistry and tease the mind with their inscrutability. Using traditional black-and-white, medium-format darkroom techniques, she’s turned day-to-day scenery and found artifacts into a compelling dream world with disconcerting undertones, not unlike the ethereal work of the late Francesca Woodman. But Vrba is still with us, emerging in the art-book world with this debut monograph.

This ambitious tome includes two books in a slipcover, both comprehensive surveys of Rio de Janeiro from prolific photographers in different centuries. Part one presents the imagery of Brazilian native Ferrez, who documented Rio in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as the vibrant city emerged within its naturally splendid environs. Part two gathers recent Polidori photographs showing the continuing majesty as well as the congestion and poverty of modern Rio, from its grand vistas to its dense favelas. What’s most striking are the similarities: Both bodies of work feature large-format panoramas (with zig-zag image combos; no photo-stitching here) and breathtaking views of burgeoning urbanity in a glorious landscape.

Here’s one of the year’s most delightfully weird titles: a glimpse behind the Iron Curtain of eastern Europe from a consumerist viewpoint. David Hlynsky traveled to seven Communist bloc nations from 1986 through 1990, aiming his lens on bizarre items in shop windows. “I purposefully avoided dramatic moments and newsworthy events,” he writes. “The banality of the shop windows underscored a real cultural difference between East and West.” Yet Hlynsky’s images teem with color and wit: graphic signage, oddball product arrangements, vintage appliances, and amusing street life. Now largely gone, these scenes are like relics. “The Cold War is over,” Hlysnsky concludes. “To the victor belong the spoils.”

Like any great dictionary, this should be the last word. At 440 pages it’s not the biggest photobook ever, but it’s one of the most fact-crammed ones. Name any imaging topic or a major artist: Go to town. Great photographs are mixed throughout. Despite an annoying repetition of digital tropes (arrow signals, highlighted text), this is a trove of wonderful work and valuable info.

Sebastian Copeland’s pictures of the Arctic celebrate its beauty—from grandiose ice formations to occasional wildlife such as polar bears, ringed seals and snow geese—yet it’s clear from these images that the scene is evolving as the ice melts. While the text (including a thoughtful foreword by Richard Branson) underlines the ecological concerns, the images show a landscape that would look absolutely awesome—if not for that visible thaw.

Ash Thayer was a 19-year-old art student when she found herself suddenly homeless after an eviction from a New York City apartment. She ended up at See Skwat, one of the many deteriorating buildings on Manhattan’s Lower East Side that had been abandoned by the city and taken over by low-income residents with nowhere else to go. She bounced between the city’s various squats from 1992 through 1998 as she finished her degree at the School of Visual Arts. She documented her life as a way to both fulfill class assignments and create a visual record of the sweat equity that residents had poured into these buildings that had essentially been left to rot. This is that record—where a post-punk subculture and arts community mingled in a wild underground milieu.

Mark Cohen has a gift for seeing the unexpected moment: the graphic pattern within a frame (as in the title) that makes you look again. Lots of these photos are blurred; others are cropped at the feet; many seem haphazard. No big. This is a deftly arranged collection of work from a gifted street photographer who’s never achieved major fame but managed to keep the flame.

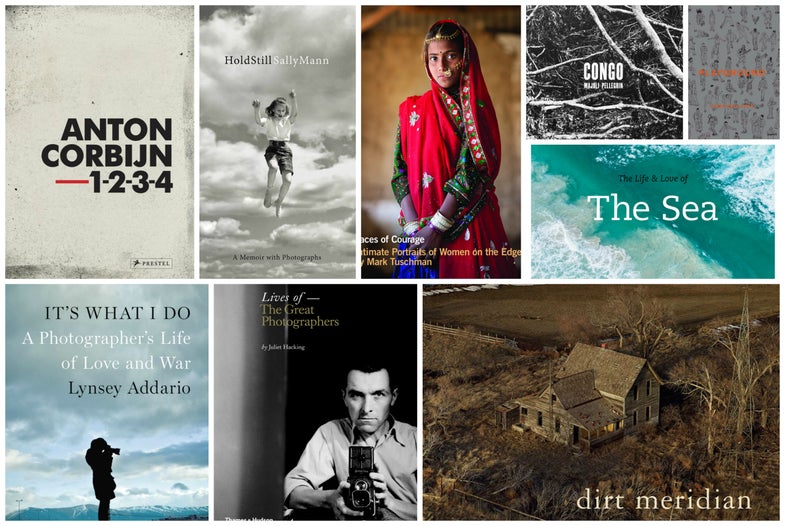

Magnum photographers Majoli and Pellegrin each bring their distinctive styles to a collaboration in which they don’t bother with individual photo credits. Nor with captions or descriptions. The dramatic pictures are left to speak for themselves—though the book comes with a booklet of text by Congolese writer Alain Mabanckou, whose poetic passages allude to the images in order (tricky to match up with no page numbers). But never mind. Just take in the powerful photos: Grand landscapes, gritty industrial sites, wild creatures, impoverished villagers, and elaborate tribal rituals all admix to reflect the complexity of the Republic of Congo (not the neighboring DRC). Mainly black-and-white with a smattering of color, this imagery conveys the stunning beauty and harsh reality of its geographic backdrop.

Shot over the past five years, Jordano’s series depicts his hometown’s long-time residents—in all their resilience, determination, and joie de vivre—often with an unflinching eye on the backdrop of their rough environs. Books on Detroit “are usually all about the abandonment and empty factories and crumbling paint on walls,” says Jordano, who now lives in Chicago. “It seems like a one-sided story.” Aside from portraits, he’s been shooting landscapes within Detroit’s city limits, concentrating on revitalization projects and empty forestry. “There were 1.8 million people living in Detroit in 1950, and now there’s 700,000,” Jordano says. “What do you do with a city that’s lost 1.1 million of its residents?”

New York–based Laub began this project as a documentation about a segregated prom while on assignment for SPIN magazine. Then in 2009, the New York Times Magazine ran the story “A Prom Divided,” which included her photographs and audio interviews of the segregated prom, igniting controversy about the school’s policy. From there the plot thickens, incorporating rural politics and murder, as evidenced in this volume (as well as Laub’s acclaimed documentary film and gallery exhibit). Anchoring it all are Laub’s empathetic portraits and eye for beauty amid the drama.

The photographic greats are here—Brassaï, Muybridge, Kertész, Bourke-White, Man Ray, Cartier-Bresson, Steichen, Mapplethorpe, Madame Yevonde—and has anyone noticed how often they have weird names? Not to mention weird lives. Which is half the fun, along with the amazing imagery that adorns each of these incisive write-ups. Do you know about Hannah Höch and Clementina Maude? You probably should…and this is where and how you can.

One purpose of this project is to signal myriad afflictions and crimes suffered by women around the world, including child matrimony, dowry abuse, teen pregnancy, domestic violence, and sex trafficking. Another aim is to spotlight hope: healthcare options, educational outreach, teachers and mentors making a difference. Underpinning both are Mark Tuschman’s warm portraits of women, children, and partners that sometimes belie the rough lives of the subjects, other times reveal them. The text details the project’s advocacy; the images reflect it.

Another title for this could be “Sad Eyes”—that’s the trait each portrait subject shares, and sometimes all you can see of their veiled faces. In Almond Garden Gabriela Maj depicts women in prisons in Afghanistan, many convicted of “moral crimes” (including victims of rape who are then imprisoned for having sex outside marriage). In a culture where women are treated as property, prison life is bleakness in the extreme—yet what comes through these images is a sense of fortitude. Maj affords dignity to her subjects. When possible, she poses them with their main reason for hope: their children. Unfortunately, though, the kids are incarcerated too.

In its title and imagery, this volume reflects the paradox of life in post-9/11 Afghanistan: the grim realities of wartime and the citizens’ resilient attempts to live normal lives. Zalmaï returns to his homeland and brings a sympathetic eye to the survivors of battle crossfire and of impoverished conditions, often in refugee camps or urban slums. Interspersed are his cheerily colorful images of commercial billboards, wedding table-settings, and other signs of modern comfort amid the squalor. It’s a revealing view of a mysterious land that perhaps only a native—who then became a visitor—could uncover.

Like the best of her photography, Mann’s memoir is undeniably personal and revealing. “It’s a deeply ethically complex situation when you’re photographing someone because you as the photographer hold all the cards,” she has said. “You always do.” This is a responsibility that Mann carries over into her writing: an unflinching honesty that makes this memoir a deep exploration of artistic evolution, familial ties, and personal growth.

Barnes has spent the bulk of his adult life on the road—traveling across the states to document America’s shrinking fringe groups. He’s hung out with bikers, Bloods, and serpent handlers. Roadbook collects 15 years of his travels in a single place. Using black-and-white film, Barnes takes an intimate look at outsider cultures that have often been misrepresented or simply turned into caricatures by the mainstream. “This is real life,” he says. “Some of those low-rider cats, that is what they make movies about, but these are the real characters.”

Andrew Moore surveys the U.S. regions along the longitudinal divide between the verdant East and the arid West—extending from North Dakota to Texas—known as the 100th Meridian. His intimate portraits bring us into the homes of families and wizened ranchers whose descendants settled the high plains generations ago. Paired with these portraits are bird’s-eye images of the Western landscape; Moore worked with a Cessna pilot he befriended to fly him around. The resulting collection tells a story both timeless and relevant.

Amid the controversy over the nuclear accord with Iran and the vilification of its leaders, it’s easy to lose touch with the country’s citizens, many of whom actually like the West. Tavakolian—who grew up in Tehran, then became a roving photojournalist but kept ties with her homeland—portrays Iran’s human side: young students, workaday commuters, celebratory families, often seeming to contrast their dreary environs. In her intro, Tavakolian calls this a document to her own generation: “This photo album is theirs; it is my vision of life in Iran now, unromantic and confined.” And fascinating.

From Italy to Argentina, Budapest to Moscow, Leventi travels the globe to present the interiors of opera houses that are nothing short of awesome. Shot in large format from the vantage-point of the stage, each image conveys the architectural majesty of its hall as the performers see it—a fitting tribute from a photographer who’s the grandson of an opera singer and the son of two architects. Ranging from the 18th-century ornateness of the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, Belgium, to the sleek modernity of Den Norske Opera og Ballett in Oslo, Norway, these opulent creations reflect the universal splendor of high society.

A daring war photographer, Lee Miller led a multifaceted professional life. She started her career as a model, worked with partner (and lover) Man Ray to pioneer surreal imagery, and photographed for Vogue and other fashion magazines. Each of her roles plays out in this volume, which shows WWII from the female side: on the home front (holding down the households and the shops); in uniform (as pilots, nurses, firewomen, etc.); keeping art and glamour alive and well throughout. While Miller’s extraordinary photos are the focus, this is really a history lesson in visual arts, entertainment, fashion, society, journalism, and world events.

The most comprehensive survey of Cecil Beaton’s career to date, this opus spans a half-century of brilliance (the pioneering lensman died in 1980). While fashion imagery abounds, we also see Beaton’s evolution from a surrealist contemporary of Man Ray and Dalí in the 1930s to a wartime chronicler in WWII to a portraitist of the stars and the royals in later years. The constant is Beaton’s uncanny ability to make everything and everyone look mysteriously sublime.

Corbijn’s grainy pictorial style has a sense of grit and honesty that fits his favorite subjects: rock-and-rollers. Best known for his image-making work with acts including U2 and Depeche Mode, the photographer/filmmaker has shot numerous characters in the music biz—from the Stones to Arcade Fire and Kate Bush to John Lydon—seemingly with their guards down, as if they’re just hanging with a friend. Among the highlights is a series of Tom Waits images—culled from the 2013 title Waits/Corbijn*—showing the visual collaborators in rare, wacky form.

On a series of road trips with his young daughter Clover, Jesse Burke creates a photo travelog of naturalistic scenes and metaphysical musings, sort of a visual version of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Inspired by familial imagery by the likes of Sally Mann and Emmet Gowin—with image titles derived from Johnny Cash songs—Burke’s pictures have a lyricism and grace that reflect the duo’s close relationship with each other and with nature, from bloody noses to dead carcasses to majestic seaside sunsets.

Mollison‘s latest project depicts schoolchildren romping on playgrounds throughout the globe; their environs vary wildly, from the wilds of Kenya to the cramped modernity of Japan, but their unbridled energy is constant. Further inspection reveals a surprising tendency toward combat—”little flashes of violence and cruelty,” as Jon Ronson notes in his intro. This is offset by all the joy on display, in Mollison’s words: “The sheer excitement of it. The lesson ends. And you just explode out into the playground, and you’re just running…”

The title Political Abstraction is apt—these are abstract renderings of day-to-day objects. The political part is the fact that Gibson shot them in eight different countries, none of which are identifiable. The message is one part we’re-all-alike and one part eye-of-the-beholder. (“The reader is the subject of this book,” notes the endpaper.) Self-published as a catalog to gallery shows, the book showcases Gibson’s trademarks: beautiful shapes emerging in the interplay among light, shadows, and objects.

Despite his considerable output and Brazilian lineage, Salgado claims he doesn’t drink coffee—but he pays tribute to java culture in this handsome tome. In ten countries throughout South America, Africa, and Asia, Salgado’s black-and-white survey glorifies indigenous field workers, lush vegetation, and time-honored brewing processes. You won’t find steaming mugs (or hipsters) here—this is all about the sustainable and ancient arts of the bean trade (or more accurately, the cherry trade). As the world around it evolves, Salgado notes in his intro, “coffee’s life cycle changes little.”

Honored with a Lucie Award as photobook of the year, this box set is a grand retrospective of Howard Schatz’s 25-year oeuvre. First recognized for his explorations of water, Schatz has studied myriad subjects from dancers to athletes, pregnant women to abstract formations, celebrities to homeless people, all with a certain graphic intensity. Collectively, the work serves as a catalog of the human body—its development, strength, and deterioration—and a glimpse into the socio-psycho realms of human experience.

In his usual oceanic fashion, Lewis Blackwell takes his photographic curatorship into the deep here, collecting work by various photographers (including Art Wolfe, Laurie Campbell, and Paul Nicklen) in a vast survey ranging from bug-eyed closeups to sweeping overviews. The text balances poetic swooning with concerned environmentalism. “Two-thirds of the earth’s surface is ocean,” novelist Haruki Murakami is quoted. “All we can see of it with the naked eye is the surface: the skin. We hardly know anything about what’s underneath the skin.”

Pritchard, director-general of the Royal Photographic Society in England, covers the full timeline of commercially available cameras—opening with the Giroux Daguerreotype in 1839 and ending appropriately with a camera-phone, 2013’s Nokia Lumia 1020. You’ll find familiar names, from the Kodak Brownie to the Leica M3 and Nikon F, each with a short history and several images. Perhaps most interesting are the obscurities—like the Enjalbert Revolver de Poche, a pistol-shaped device which produced images on tiny glass plates within its barrel. The book uses each camera as a jumping-off point to discuss a moment in the medium’s history and the people who made use of the technology.

Ali Hadi, a professional body washer, prepares the body of a bombing victim for Muslim burial as the man’s relatives watch in Najaf, Iraq.

Over a span of 15 years, Shields has culled dozens of war images from the front pages of the New York Times—mostly in Iraq and Afghanistan—which are easy on the eyes. “Something started to gnaw at me: Am I just imagining that these photographs are more beautiful than they should be?” he says. “These are virtually war-recruitment posters. They make it look cool.” Shields presents 66 images that illustrate his critique, with chapters arranged around what he calls “tropes” of war imagery—”Nature,” “Painting,” “Pietà,” “Movie,” “Love”—and illustrative examples. Shields puts his critique not on combat photographers but rather “squarely on the desk of the photo editors, news editors, and art directors who seem to be stressing beauty over truth-telling.”

Photography’s rich history and creative doers continually make it clear: The best place to see great images (aside from a museum or gallery wall) is a bound book. In the holiday spirit, we’ve drawn this list from recent releases as well as our roundups in spring, summer and fall. —Jack Crager