Adamant Eve

When Eve Arnold passed away in London on January 4, some three months shy of her 100th birthday, she left...

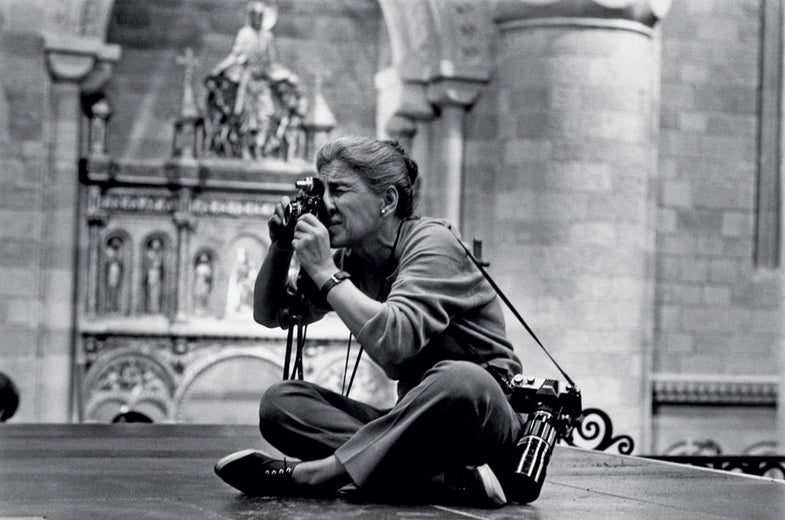

When Eve Arnold passed away in London on January 4, some three months shy of her 100th birthday, she left behind one of the most impressive photographic legacies of the 20th century. Her most famous work documented the private lives of megacelebrities. Her most important work documented the private lives of the disenfranchised. And her career—begun in an era of tremendous discrimination against women and ended as one of the most highly acclaimed photojournalists in the world—traced a similar swing between poles.

Born Eve Cohen in Philadelphia on April 21, 1912, Arnold’s parents were Russian Jewish immigrants who came to the United States to start a new life. Her interest in photography was piqued in the early 1940s, when she worked for film finishing firm Stanbi Photos in Hoboken, New Jersey. She followed her gut to a six-week photography course at the New School for Social Research in New York City. The class was taught by renowned Harper’s Bazaar art director Alexey Brodovitch, and Richard Avedon numbered among her classmates. It was as a student there that Arnold was inspired to begin the project that would propel her into the world of professional photography: a series on the fashion shows being run in deconsecrated churches in Harlem. About the work, Brodovitch reportedly told her, “You go back to Harlem and stay with it.”

Stay with it she did. Over the next year and a half she made the trek uptown again and again to capture the kaleidescopic eruption of passion and creativity going on there. In 1951 her photos appeared in Picture Post, where they garnered immediate acclaim. For her next project, in a theme that would become familiar, Arnold took a complete left turn, creating a series on black migrant laborers on Long Island. That same year she became the first woman to join the Magnum Photos agency/collective (Inge Morath would follow her in 1953). She became a full member in 1957 and took an active role mentoring other exceptional women photographers.

“She was very encouraging when I tried to imagine myself in Magnum,” says Susan Meiselas. “Some of my favorite moments were dinners with Eve, Inge Morath and Martine Franck, where we would catch up on our lives. Eve was a single mom for a great part of her life. Still, she managed to do all she hoped to do in her life.”

Under the aegis of Magnum she travelled the world, shooting in Cuba in 1954, Afghanistan (with special emphasis on its women) in 1969 and Communist China in 1979 (one of the first western photographers to do so). Looking at her work as a whole, it’s hard not to viscerally feel her wanderlust and drive. The subjects she captured were as varied as their locations, ranging from the raw social issues of the downtrodden and impoverished to the fiery politics of the day to the glamour of the cinema (she was especially known for her intimate portraits of Marilyn Monroe). As she told the BBC in a 2002 interview, “If you’re careful with people and if you respect their privacy, they will offer part of themselves that you can use.”

Her seamless objectivity, moral convictions and technical rigor distinguish her work almost automatically. Looking at her photos, it’s apparent that her intent to capture raw, candid and intimate portraits was present irrespective of whether the subject was Elizabeth Taylor or a Mongolian girl lying on the steppe with her horse. As Magnum cofounder Robert Capa put it, her work “falls metaphorically between Marlene Dietrich’s legs and the bitter lives of migrant potato pickers.” Indeed, searching for the numinous amid the quotidian remained an abiding quest throughout her career. As she’s been quoted: “It’s the hardest thing in the world to take the mundane and try to show how special it is.”

That fascination drove her as a clinical yet empathic documentarian. “If a photographer cares about the people before the lens and is compassionate, much is given,” she noted. “It is the photographer, not the camera, that is the instrument.”

Arnold approached her work with movie icons such as Marlene Dietrich, Joan Crawford, Clark Gable and John Huston with the same photojournalistic objectivity with which she tackled a Harlem fashion show or a Little League baseball team. Her candid on-set shots were a radical departure from the usual glossy studio-system images of the era, but Arnold was not about to bend to anyone’s will where her photos were concerned. As Giles Huxley-Parlour, director of Chris Beetles Fine Photographs, which recently exhibited her work, notes, “Arnold thrived in the golden age of photojournalism, when publications gave photographers great resources and freedom to practice their art.”

In all her endeavors, it may be said, Eve Arnold was a passionate, funny and determined individual who tirelessly gave her craft to the world. “Her generosity to younger photographers and to the collective is the strongest memory that keeps coming back to me,” says Meiselas. “She chose her own path, her own work. She was constantly making calls, setting up arrangements; she did it all. That was inspirational to all of us.”

As her long-time gallerist and close friend Zelda Cheatle puts it: “Imagine a little silver-haired person with a deep laugh and twinkly brown eyes, and you begin to have a picture of this tour de force who traveled alone in strange and sometimes hostile environments, undeterred by anything, whether a hurricane gale blowing in Cuba or supporters of Malcolm X wanting to stub out their cigarettes on her back. She effortlessly glided into palaces, film sets or yurts, council flats in London’s East End or Salvation Army hostels.

“I think of Eve working, working, working. If she was not out and about photographing, then she was writing and captioning and planning ahead. She had a big, long wooden table, and I think of Eve and Linni, her assistant of 40 years, laughing and working and sifting through prints and transparencies, Eve writing and writing. Eve Arnold loved life. We are all lucky that her pictures will live on.” AP