Explore the gauges, levers, and history of a 747’s iconic cockpit

We spoke to pilot and author Mark Vanhoenacker on the flight deck of a classic jumbo jet.

The cockpit of a British Airways Boeing 747-400 is a beautifully complex place where a handful of analog gauges live side-by-side with digital displays.

Among the vast array of system switches and controls in the worn flight deck, some parts are easier to understand than others. Four Rolls Royce engines power the giant 747 aircraft, hanging off wings that span about 211 feet—and in the center of the cockpit are four ivory-colored thrust levers, one for each engine.

I’m a journalist, not a pilot, but I’m sitting in the captain’s seat on the left side of the flight deck. Mark Vanhoenacker, a senior first officer with British Airways, author of air-travel books, and a columnist for the Financial Times, is in the seat to my right.

“It’s as basic as it can be,” Vanhoenacker says casually, then pushes those four thrust levers forward with one hand. A moment later he moves them back where they were. “Push them forward, you go faster; pull them back, you go slower.”

Our airliner’s parked at a gate at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City, and the engines are off, so of course, we don’t change speed. Earlier that morning, the vessel had flown in from London’s Heathrow, typically a seven-hour-plus flight. Later that day, it will cruise back.

I’m there to talk to Vanhoenacker about his latest book, How to Land a Plane, but also—let’s be honest—to just spend some time in the cockpit with a seasoned aviator who showed me some of its cavernous interior during an interview in late May. To be in a 747 meant the chance to see the nerve center of an iconic aircraft up close—a plane that’s the basis for Air Force One, that people love flying in and staring at, and that helped make air travel more affordable—as airlines fly them less and less. (Vanhoenacker doesn’t fly the 747 now; other pilots steered the plane in from London that day.)

Sitting in the cockpit, some of the flight controls are easy to grok, even for a person who’s never ferried hundreds of passengers through the skies. Both seats have a control column in front of them, with a wheel, on top. Pull the wheel and the column back towards you, and the plane’s nose pitches up. Push it forward, the reverse happens. Turn the wheel to the left, and the plane banks left. A pair of pedals at each of our feet control the rudder.

A single small lever, with fading green paint and a miniature wheel on the end, raises and lowers the enormous aircraft’s landing gear. (Get it—a lever with a little wheel on it controls the wheels?) Another lever with a handle shaped like a wing controls the craft’s flaps and slats, which allow the plane to generate more lift and thus fly more slowly. Upon it is simply written “FLAP.”

We each have a monitor in front of us—the primary flight display—that indicates in colors such as green, purple, and blue crucial information like the aircraft’s airspeed and altitude. Not far from those screens are three classic-looking gauges that duplicate that information in analog form. They’re a form of redundancy, which is the name of the game in aviation.

“This is almost literally what you’d see on a Cessna,” Vanhoenacker says, pointing at those gauges.

But this is no Cessna. For one, it seats 275 people, measures about 232 feet from tip to tail, and cruises at 85 percent of the speed of sound. For another, the flight deck boasts a small bunk room that sleeps two, plus a lavatory, so the crew don’t need to leave the cockpit for a bathroom break.

This particular 747 first flew in 1999. In 2019, it’s not ancient—but it sure does look old, in a capable, dad-bod kind of way.

Let’s land this baby

Vanhoenacker’s latest book, How to Land A Plane, is a good choice for anyone who’s fantasized about suddenly having to get an aircraft safely down on the ground; the book will tell you some of what you need to know.

“Spoiler alert,” Vanhoenacker says before we get on the plane. “You cannot learn to land a plane by reading a book, but hopefully it’s a fun way of thinking about what pilots think about all the time.”

And indeed it is: The slim volume walks you through some of the basics of flight and landing, from how to recognize a cluster of instruments known as the “six pack” to knowing what purpose the PAPI lights near the runway serve.

How to Land a Plane follows Skyfaring: A Journey with a Pilot, which The New York Times said “makes jet travel seem uncanny and intriguing all over again.”

“I was thinking that there is that poetic side of flying,” he says, “and then there’s also a really, really technical side, and very, very mechanical side.” This new book is all about that practical side.

And on the subject of landings, keep in mind that there’s a good chance that every landing you’ve ever experienced on a commercial flight has been executed by a pilot actually landing that plane by using the flight controls (unless you regularly fly in and out of an airport frequently socked in by fog, like in London or Delhi). In a world of autopilot, artificial intelligence, and self-driving cars, some might assume that planes are constantly landing themselves. And while they can, it’s rare that they do.

The main reasons an airliner will land itself is if the runway is enveloped in fog or flying snow so thick that a pilot can’t see the tarmac. And setting that process up is a pain. “When we get a weather forecast that reports that kind of fog, there are groans in the fight deck, because it’s a lot more work to land it automatically,” Vanhoenacker says. It’s rare to do that—he estimates it happens just once a year for him. And airliners don’t ever take off automatically, either; the pilot always flies it off the runway.

The autopilot does, however, allow pilots to program the route into the aircraft in advance, so that the plane automatically makes the turns it needs during the cruise phase of the flight. That type of assistance frees up cognitive bandwidth for pilots, who need to consider other factors, like what to do if a passenger gets sick or if they need to land elsewhere. In essence, it allows the crew to focus on the “overall management of the flight,” Vanhoenacker says—the mundane yet essential stuff like making radio calls or picking a new route.

An aircraft for “thin” routes

Vanhoenacker flies the 787 Dreamliner, a more modern and fuel-efficient airliner, now. His new aircraft is advanced enough that the pilot can use a cursor on a screen to tell the plane where to go. “On the navigation display, you can see it’s painting where the storms are, and you can point and click to a position away from the storm” to direct the plane there, he says. “The 747 does not do that.”

When you switch the autopilot off, a quick and repetitive siren-like thrum plays to alert the pilots.

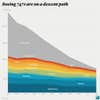

Airlines like British Airways and Lufthansa still operate 747s, but the giant four-engine planes are on the decline. From a financial perspective, carriers may prefer more fuel-efficient two-engine craft like the Airbus A350 and the 787, which are also smaller than huge planes like A380. (Boeing still makes the most modern version of the 747, the 747-800, but the orders they have on hand are for the freighter version.)

A rule of thumb for fuel consumption on a 747 is that it will burn about 11 tons of fuel per hour. The 787 burns about half that in the same period but still carries more than 50 percent of the passenger load of the 747. “Most airlines are laser focused on managing fuel consumption,” says Andrew Buchanan, a vice president at Oliver Wyman, a firm that consults for airlines. That, and Buchanan notes that aircraft like the Dreamliner are good for what he describes as “long thin routes”—an epically long journey that skips the traditional hubs and doesn’t carry as many people as an Airbus A380 would. Example: Air New Zealand operates a long flight between Chicago and Auckland on a Dreamliner.

In other words, the aviation landscape has changed since Barry Lopez, in his classic 1995 essay titled “Flight” for Harper’s magazine, wrote: “The Boeing 747 is the one airplane every national airline strives to include in its fleet, to confirm its place in modern commerce, and it’s tempting to see it as the ultimate embodiment of what our age stands for.”

Fly-by-wire

Another major difference between a 747-400 and the Dreamliner is that the latter is what’s known a fly-by-wire aircraft. In the 747-400, when the pilot moves the controls, actual physical cables convey that motion to the rest of the plane, so the surfaces on the wings, like ailerons, can move appropriately. On a fly-by-wire plane, those instructions are passed electronically—that’s the “wire”—along to the rest of the plane. In brief, on the Dreamliner and others planes, computing power sits between the pilot and the actual motion of the aircraft. On our 747, it’s mechanical. (Boeing 747-800s are fly-by-wire.)

Being back in a 747 is enough to trigger some serious nostalgia for Vanhoenacker, who flew them for about 11 years. “We’re sitting on the flight deck of this totally iconic, beautiful aircraft that changed the world,” he reflects; it’s a plane famous enough to have flown its way into the lyrics of songs by the likes of Joni Mitchell and played a key role in the film Inception.

“I will never sit in this seat again in my life,” he adds, as our time in the cockpit draws to a close, unless he happens to show another curious journalist like me around. “It’s sad, isn’t it?”